This is the Nobel Museum, housed in the old Stock Exchange building right in the shadow of Storkyrkan‘s baroque steeple. It is right in the heart of Gamla Stan, looking out over the cobbles of Stortorget just a short walk up the dappled lanes from Vasterlangaarten. In the bright morning light of my last day in Stockholm, it stood still in the quiet of the square, understated with hardly a hint of the inspiration within.

I entered the cool dark hall, the gentle flow of past laureates above my head and glowing pillars forming a gentle arc around the atrium to honour this year’s winners. Come November they will join the parade of banners overhead to be replaced with a new batch of those deemed to have made the most significant difference over the last twelve months.

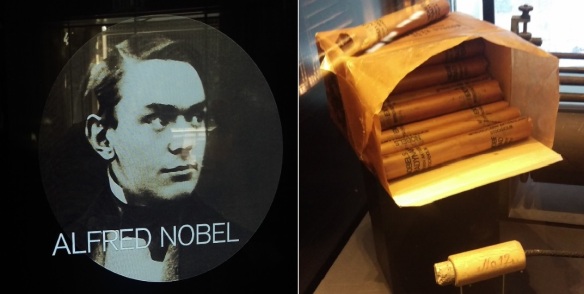

The original ideas man

Alfred Nobel was born in Sweden in 1833 and had a well-travelled life. He spoke four languages even as a child and throughout his adult life, spent his time most notably in St Petersberg, Stockholm and Paris. He was a descendant of Swedish scientist Olaus Rudbeck and it would appear that invention flowed down the bloodline with Nobel’s father, Immanuel being the inventor of modern plywood and an alumunus of the Royal Swedish Institute of Technology. Alfred himself had a mind that constantly sought solutions and he had 350 international patents awarded in his lifetime, the most famous of these inventions being dynamite (1867), gelignite (1875) and the predecessor to cordite, ballistite (1887).

His legacy is twofold. He built an international business empire with interests as far-reaching as Australia, Japan and North and South America as well as closer to home in Europe and Russia and it lives on in numerous companies world-wide. (Heard of chemicals giant Akzo Nobel?) Needless to say, Alfred Nobel left a considerable estate upon his death in 1896.

The Nobel Prize was defined and instructed through Alfred Nobel’s last will and testament. His vast fortune was to be held in secure investments and used to fund five prizes each year celebrating…

“…those who, through the preceding year, shall have conferred the greatest benefit upon mankind.”

The five prizes, in areas that held the most fascination and interest for Nobel, were to be awarded by the institutions he held in the greatest esteem. The Nobel Prizes for Physics and Chemistry were to be conferred by The Swedish Academy of Sciences, the Nobel Prize for Physiology or medical works by the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, the Nobel Prize for Literature by the Swedish Academy and the Nobel Peace Prize by the Norwegian Storting.

However these organisations were unaware of Nobel’s final wishes and it took the creation of the Nobel Foundation and a further five years before the first prize was awarded in 1901. In 1969, a sixth prize was awarded – the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel – but while conferred by the Swedish Academy of Sciences at the same ceremony as the other prizes, it is funded by Sweden’s central bank and is not deemed a Nobel prize.

Nobel endeavours

I wandered from room to room, watching interviews and footage of just a small number of prize winners. Between 1901 and 2014, 567 prizes have been awarded to 889 laureates who, in leaving their particular legacy, have allowed mankind to continue to fashion its future. The soft click overhead heralds the breathy release of a prize winner’s banner on the cableway – each glides noiselessly around the ceiling of the exhibition hall before joining the others again. It’s an ingenious way to make sure that every laureate can be honoured here yet with plenty of space for those still to come. A video installation, shrouded in diaphanous white folds, explores the future with 19 laureates – what is their hope? – and the importance of passing something on.

Exploring ideas has laid foundation after foundation for the discoveries of today and underpins our society’s progress and it is an awesome thing – that one man’s passion for ideas and his belief in human creativity more than one hundred years ago lives on in celebrating those who exemplify his credo in their work, their commitment and in the people who inspire them. My two and a half hours here left me feeling humbled and moved by people’s extraordinary-ness and I emerged from the cool semi-lit hall into the afternoon sun quiet and contemplative.

I sat in an outdoor cafe, reading the small booklet about Alfred Nobel that I’d purchased on my way out and as I finished and moved to close the back cover, I noticed the words that lay below the image of that legendary golden medal:

The Nobel Museum – ideas changing the world

Long may it continue, I thought.

Long may it continue.